Why We Need More Hostile Takeovers

Despite what critics say, it’s good to be hostile. It frees you to do what’s right rather than what’s popular or politically correct; which – quite frankly – in the long run, is always more important than being the toast of the golf course. That’s right, dusting off and reaching deep into the corporate raider toolbox is actually in the common good and national interest.

Ever since the Enron scandal burst into the public view 16 years ago, there has been an unhealthy appetite for all kinds of new regulations designed to protect investors. Never mind that these regulatory Washington quick fixes are cooked up by politicians and lobbyists who conveniently ignore the following painful fact: Both Enron as well as more recent corporate meltdowns are the direct result of regulatory and judicial efforts to restrict hostile takeovers almost 30 years ago.

As an unapologetic proponent and practitioner of this so-called “dark side” of investing, it is reasonably unfortunate to see that politicians still haven’t learned just how massive the cost of suppressing beneficial market forces can be.

The powerful league of extraordinary critics – which includes top-tier auditors, lawyers, investment bankers, independent directors, and government officials – is heavily incentivized to push proposals that strategically sidestep the real problem and tip the balance of regulation in favor of corporate management.

Hostile Takeovers To The Rescue

It should come as no surprise to anyone that new corporate scandals will continue to rear their ugly heads and devastate stakeholders across the continuum of the economy until we rediscover and take advantage of the most powerful market mechanism to eject entrenched corporate management. Even Warren Buffett agrees that, by and large, hostile deals are a net positive. Berkshire Hathaway wouldn’t exist without one.

The principle behind hostile takeovers is simple. If a public company is badly enough managed, its share price will decline and underperform its competitors as displeased investors start to exit their investments. At this point, the ensuing value dislocation can create a profitable opportunity for a fresh set of investors to make a tender offer and bring in new leadership.

According to Bloomberg Gadfly columnist Brooke Sutherland, takeovers that start out unfriendly, or turn hostile, generate better returns for the acquirer, on average, than deals where the buyer and seller are in agreement the whole way through. Put another way, bad blood is a good thing.

As you may have already guessed, just the mere threat of a potential hostile takeover will provide a compelling incentive for managers to live up to their responsibilities.

History Of Hostile Takeovers

The concept of the separation of corporate control and ownership dates back to the 1930s and was explored by Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means in their book The Modern Corporation and Private Property. Berle and Means argued that the management of public companies could exploit their positions as insiders to deceive and defraud shareholders since they were not subject to effective monitoring.

What if public companies could be made more democratic? What if shareholders could junk bad managers with a simple majority vote?

It took almost 30 years for the other shoe to drop and the concept of a market for corporate control to gain acceptance. In the 1950s, economists began to challenge the notion that public companies were, in a sense, political institutions best suited to be governed by purely democratic forces.

What followed was the realization that public companies are, for better or worse, just a creation and function of the marketplace.

The underlying separation of corporate control and ownership problem – better known as “agency cost” in corporate governance parlance – was viewed for the most part as fundamentally agreeable to the forces of a market for corporate control.

During the 1950s and 1960s, hostile takeovers stress-tested the largely unregulated market for corporate control while shareholders of target companies received, on average, a 40 percent premium over the pre-bid price for their shares. Of course, the gaggle of threatened CEOs and their well-paid advisors became so enraged that Congress had to take action, which culminated in the passing of the Williams Act in 1968.

Gone was the element of surprise that was so cherished in many hostile takeovers.

It’s Good To Be A CEO

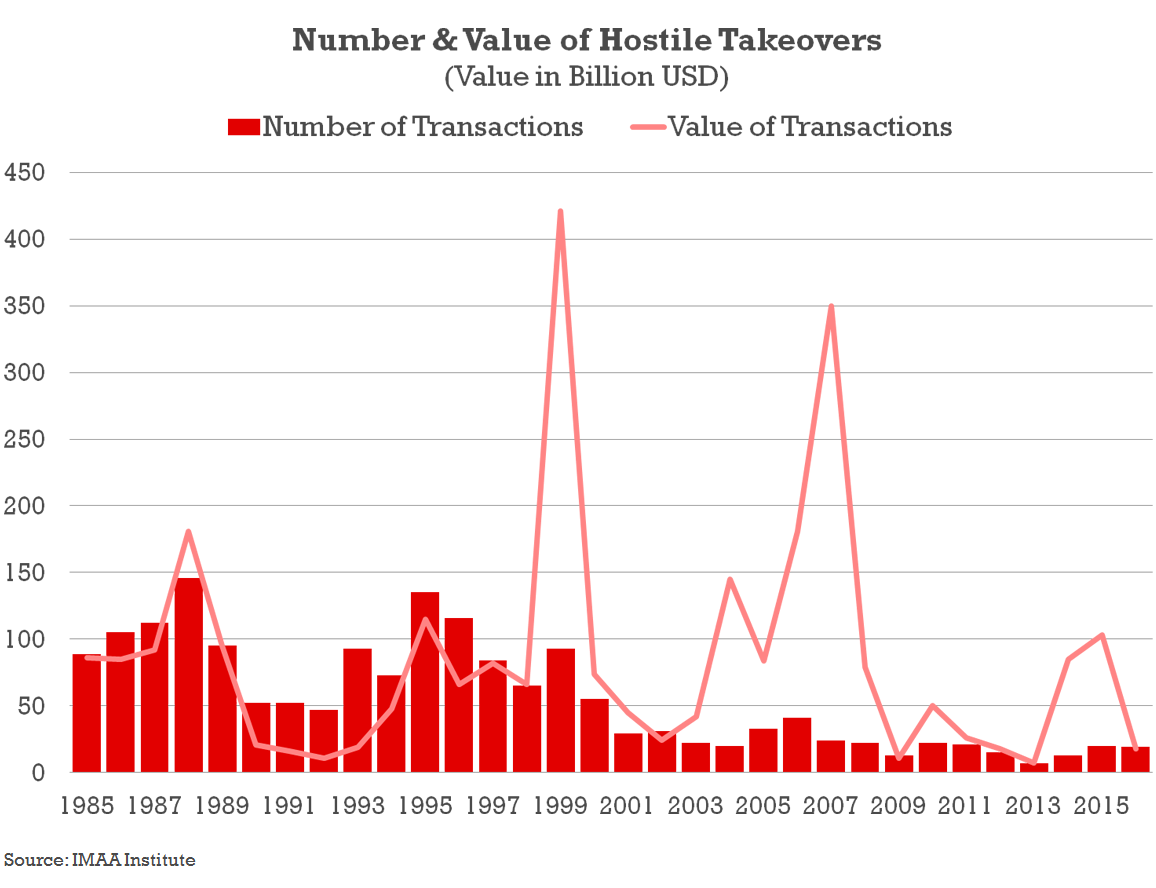

After a short-lived renaissance in the 1980s, the number of hostile takeovers continued to decline sharply due to new layers of regulation designed to kill one of the most effective free market solutions for policing the management of public companies.

Critics of hostile takeovers will be quick to point out that although the threat of hostile tender offers has been more or less neutralized, the change of corporate control process continues to thrive in the public markets.

This is true; but now, with the balance of regulation favoring corporate management, managers – rather than shareholders – collect a disproportionate share of any premium paid for a change in control. It’s worth noting that this is the same premium that has been build up and accrued by their own bad management.

The premiums paid by the acquirer will always include generous executive compensation packages that benefit management. These exit arrangements can take a number of forms, including lucrative consulting deals, stock or stock options in the acquiring company, “golden parachute” type severance packages, bonuses, or some combination thereof.

The Long Decline of Hostile Takeovers

In the last 30 years, hostile takeovers have declined by 82 percent while executive compensation went on a record-breaking tear that defies all modes of good sense and logic. How is it that CEO pay managed to increase by over 940 percent since 1978, while average worker pay has only increased by a little more than 10 percent?

There’s no arguing that CEO pay has risen far in excess of any measure of productivity even though the opposite has been happening across most of the rest of the labor market.

And while this trend is unlikely to reverse itself anytime soon, it’s clear that the profusely storied abuses alleged to result from an unfettered takeover system were far less costly to society – both in economic and social terms – than what has occurred since.

The lesson here is very simple, but it’s striking how often it is overlooked. Every piece of regulation that is designed to deter the effective functioning of the market for corporate control raises the real cost of pushing out bad managers. What’s even more perverse is that every additional increase in these costs can be claimed by entrenched managers through greater rewards to themselves and by instituting wasteful management policies.

No need to be alarmed if you’re a self-serving CEO. As long as the cost of your wastefulness doesn’t exceed the cost of a successful proxy contest or takeover fight, you’ll continue to be secure in your position – at least until the entire house of cards collapses.

For everyone else, major corporate bankruptcies and management scandals will continue to be an unfortunate yet inevitable end result of regulations that prevent the efficient functioning of the market for corporate control.

Benevolent Hostility

Nothing good ever comes from restricting shareholder rights and diluting management accountability. Not only does it reinforce bad behavior, but it also stifles innovation, efficiency, and competitiveness – qualities we need more of, not less, if we want to grow our economy and stay ahead of the curve.

The truth is, hostile takeovers will always be the Huitlacoche of public markets. To some, the gray-black corn smut is a notable functional food with bioactive substances that are used in fortifying and enriching other foods. To others, the gnarly delicacy will never be anything more than a parasitic fungus.

No matter what your dietary preferences are, we all can benefit from a more sustainable economy. Without an effective free market solution for policing corporate management, American corporations will always be at risk of making headlines for all the wrong reasons.

We need to tilt the balance back, and away from corporate management. This reversal in regulation would not only reverse the problematic trend in executive compensation but also reduce the incentive for aggressive and “creative” accounting while freeing management to focus on real growth rather than financial engineering.

Hostile takeovers might not be the most attractive looking corporate governance delicacies, but they are unquestionably functional, which is more than what can be said about a lot of CEOs and corporate boards these days.

Related Articles